The introduction of the Directive on gender pay and transparency puts an emphasis on greater transparency of remuneration, and will force companies to take actions to mitigate the pay gap. According to the Directive, the companies employing more than 250 people (and ultimately, after the full period of implementation – those employing more than 100 people) would be obliged to report data on the pay gap. Additionally, those reporting a wage gap higher than 5% will be required to conduct a salary review.

According to current Eurostat and OECD data, the gender pay gap in Poland was 5.4% in 2021, 6.5% in 2020, and 8.5% in 2019. This does not mean that the gap closing to 5.4% fully reflects the scale of this phenomenon, but rather shows the trend. A satisfactory result at the level of the entire country does not mean there are no challenges at the level of individual companies or even sectors.

From the perspective of a company preparing to address the issue of fair remuneration, it is important to understand how objective criteria, which may include education, occupational and training requirements, skills, effort and responsibility, work performed and the nature of the tasks determine remuneration, and to what extent its level depends on the gender. Such an approach can be found in the Directive on equal pay and transparency or methodologies for certification of equal pay such as Equal Salary Certification.

Making equity a reality

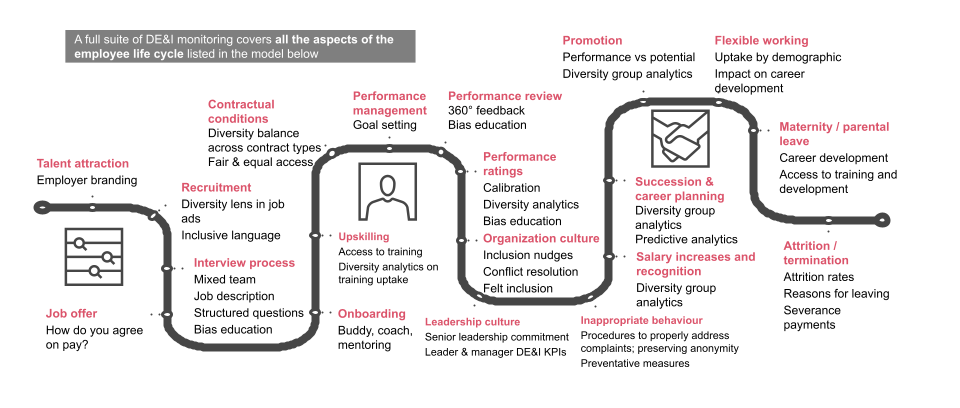

Ensuring equal access to opportunities and resources is an answer to address the gender pay gap. Equity can become a reality; if we start looking at it through the prism of the employee’s lifecycle we realise that:

- it strengthens the employee’s sense of integration and belonging

- line managers have the greatest impact on employees’ experience of the work environment

- employees pay attention to the added value the employer brings to society and to their lives

- a comprehensive approach to the area of equal treatment and equal pay is required

For organisations that wish to address the gender pay gap challenge, coping with the salary process on its own is not enough to introduce sustainable solutions. In fact, the level of remuneration of an employee is always a consequence of several factors resulting from different HR processes. We may look at them in a more detailed approach based on some real-life examples.

Recruitment

In the face of a more challenging labour market, more and more organisations face a situation where the salary expectations of a given candidate may exceed the planned budget. Therefore, recruiters often decide to ask the candidate for an expected salary rather than to follow the salary brackets defined by the company, and proactively propose the salary level.

While this approach is quite common and seems to be reasonable from the perspective of necessity to have control over recruitment budget, it may have a negative effect on the pay gap.

As shown in the studies, women more often tend to underestimate their chances in negotiating the salary during the recruitment process and on propose lower salary levels than their male colleagues. While beneficial from the budget perspective, this leads to a situation when from the first day of work the company may note differences in salary levels between men and women. This mechanism preserves the pay gap even in the situations where in other HR processes the organisation puts effort to ensure that men and women are treated equally.

Performance

The discretionary incentive schemes in general bear the risk of negative impact on pay gap as the decision may be influenced by unconscious biases that we all have. However, even if the bonuses are granted on an objective basis, the risk of unfair treatment still exists.

Imagine an organisation having a widespread network of field-sales persons whose incentives are based on a percentage of their sales. At first sight, there is no room for mistreatment. However, if we look closer and consider some factors that may be different for men and women, we will unveil the mystery.

In our real-life scenario, newly hired sales persons were allocated to peripheral areas which were less profitable. Based on good performance, they were able to move closer to the big cities. According to the studies, the pandemic has only intensified the traditional workload of women in two jobs: business and private. Women are more often required to dedicate more time for home duties. Thus, women sales persons were not able to dedicate enough time to develop sales relationships in the peripheral areas. Therefore, they struggled more to be promoted to more lucrative areas and their bonus levels were lower. At the same time, women that achieved the possibility to move closer to big cities were just as good sellers as their male colleagues.

Promotion

Pregnancy is usually a significant gap in women’s curricula vitae. In some organisations the impact of this employment gap is even more visible in the promotion progress than would be expected from the duration of maternity leave itself.

Imagine a female employee that is absent from work because of pregnancy before the performance process is completed. She may miss the opportunity to get promoted before her leave. Usually she will miss another process during her leave. To add to that, sometimes she will not get promoted also in the first performance process after her return. Because she is not present at work for a significant part of the performance period, she may miss this promotion opportunity as well. This way only a year long absence may influence the promotion possibilities even for three years.

It should be recognised as good practice that more and more organisations realise that this mechanism exists and introduce measures to avoid it.

There is no equality without strategy

The aforementioned situations are only examples of matters that may be relevant to address gender inequalities in the organisation. The introduction of an equal opportunities approach that will be in line with regulations and employees’ expectations requires a strategic approach based on goals, measures and specific actions.

In 2022, PwC surveyed European organisations on DE&I topics. While DE&I is a stated value or priority area for 85% of organisations, 31% of respondents still feel lack of diversity is a barrier to employee progression at their organisation. It means that European organisations are struggling with understanding the benefits, as well as with helping to translate DE&I strategy into action.

Additionally nearly half the organisations surveyed (49%) leverage their DE&I programme to attract talent. Less (20%) are connecting them directly to achieve business results, such as innovation or improved financial performance. This shows how this area is still intangible for many. So what can an organisation do to become a leader in it?

The first step is to review your DE&I strategy. Review the development, governance and implementation to ensure that the strategy is robust and appropriate for your organisation and it addresses your real needs.

The second step is to review HR processes with the DE&I lenses on. This review should be aimed at understanding how different solutions in your organisation influence diverse groups of employees, whether they address DE&I good practices and appropriately embed DE&I perspective.

Diversity, which serves the organisation, creates a pool of diverse talents and brings the ability to look at things from different perspectives should be natural for organisations. This means that it should come from the needs and challenges of the particular company and should not be a mere copy of fashionable actions and statements.