- Executive Note

- Editorial note

- Interviews

- Green transformation

- Events Coverage

Can climate change litigation reach where states or policymakers cannot?

White & Case | Dec 12, 2022, 19:57

By Karolina Brzeska, advocate, and Maja Pyrzyna, trainee, Dispute Resolution practice, White & Case

During the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, environmental protection policy was elevated to the rank of a basic state function. Since then, the number of more or less binding international climate policy declarations has been steadily growing with the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement among the most significant. Despite this, those efforts have not brought about either a noticeable slowdown in global warming or the creation of a realistic action plan to help achieve this goal. Consequently, the issue of climate change has remained a recurring leitmotiv rather than a part of a truly global programme. This can be at least partly explained by the inability of nations to reach a binding international agreement on this issue.

An important result, albeit possibly only a side effect, of the numerous attempts to reach internationally binding agreements on climate change has been an increase of the number of local programs to support climate change management and legislation creating a legal framework for real political action.

According to the London School of Economics (LSE) policy report ‘Global Trends in Climate Change Litigation: 2021 Snapshot’, in 2021 every jurisdiction in the world had at least one climate-focused law or policy, while some jurisdictions had well over 40. However, recent years have shown that states enjoy quite broad discretion in executing climate policies. There is no higher authority that can enforce the implementation of these laws and policies, or punish states that fail to implement them.

Partially in response to this, climate change issues have made their way to courtrooms. As the 2020 edition of the above-mentioned LSE policy report stated, the year 2019 turned out to be ground-breaking, primarily due to the increase in litigation by environmental activists and advocacy groups.

Regulation through litigation on the rise

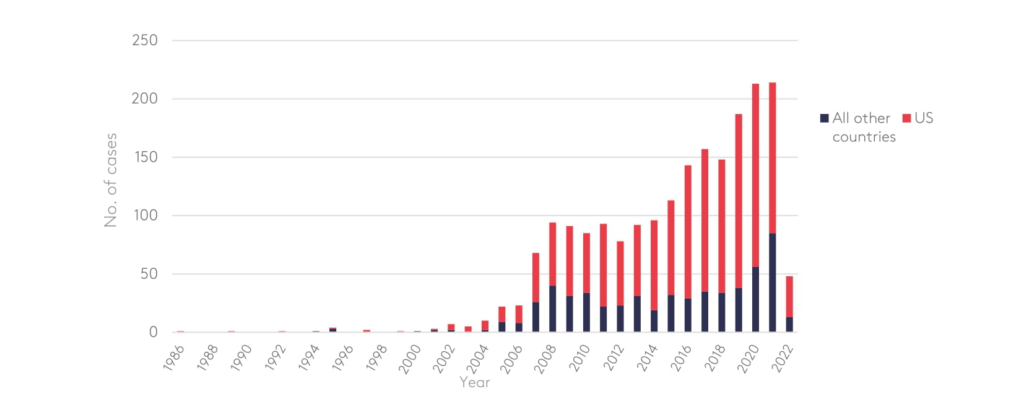

As defined by the LSE, ‘climate change litigation’ encompasses a wide range of cases brought before administrative, judicial and other investigatory bodies (both domestic and international), which raise issues of law or fact regarding climate change. Most of these cases seek to advance or enforce climate standards, drive behavioural shifts or seek compensation for failure to adapt, but some can be hardly deemed to be climate-aligned. As of 31 May 2022, there were around 2,000 climate change cases globally and this number is steadily growing:

Figure 1 – based on data available in Global Trends in Climate Change Litigation: 2022 Snapshot

A review of just a few examples of such cases (see below) can give us a taste of what can be expected in the near future.

Government framework cases

Urgenda Foundation v. State of the Netherlands

As a result of the Urgenda Foundation’s and 900 Dutch citizens’ lawsuit against the Dutch government, in 2015 the court in The Hague ordered it to limit greenhouse gas emissions to 25% below 1990 levels by 2020, finding the government’s existing pledge insufficient to meet the state’s fair contribution toward the goal contained in the Paris Agreement. Despite the Dutch government’s appeal, in October 2018 the Hague Court of Appeal upheld the district court’s ruling concluding that by failing to reduce greenhouse gas emissions the Dutch government was violating its duty of care under Articles 2 and 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. On 20 December 2019, the Supreme Court of the Netherlands upheld this landmark decision.

Carvalho and Others v. The European Parliament and the Council

In July 2018 ten families brought an action in the EU General Court arguing that the EU’s existing target to reduce domestic greenhouse gas emissions by 40% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels is insufficient to avoid dangerous climate change and threatens the claimants’ fundamental rights of life, health, occupation, and property. In May 2019, the EU General Court dismissed the case stating the claimants did not have standing to initiate proceedings since they were not sufficiently and directly affected by EU policies. Despite the plaintiffs’ appeal, in March 2021 the European Court of Justice upheld the General Court’s order and held the claims inadmissible.

Sharma v. Minister of Environment of Australia

In May 2021 the Federal Court of Australia found that the environmental minister has a duty of care to protect young people from harm caused by climate change. However, in March 2022 the Federal Court of Australia rejected the novel duty of care. Subject to an appeal, this decision may have a significant impact on government decision-makers when considering whether or not to approve emissions-intensive projects.

Corporate framework cases

Milieudefensie et al. v. Royal Dutch Shell plc.

In April 2019, a group of non-governmental organizations and over 17,000 Dutch citizens sued Royal Dutch Shell plc to oblige it to reduce its CO2 emissions by 45% by 2030 compared to 2010 levels, and to zero by 2050 (in line with the Paris Agreement). In 2021, the Hague District Court ruled that Shell had a duty of care under Dutch law, which implied an obligation not only to reduce the CO2 emissions of the activities of the Shell group, but also those of its suppliers and customers. Shell filed an appeal in March 2022 arguing that addressing climate change requires co-ordination and that the court did not consider its Powering Progress strategy released earlier this year.

Luciano Lliuya v. RWE

In November 2015, Luciano Lliuya, a farmer from Peru, filed a claim for damages against RWE arguing that RWE had knowingly contributed to climate change by emitting substantial volumes of greenhouse gases, which led to the melting of mountain glaciers and increasing water levels. The claimant asked the court to order RWE to reimburse him for a portion of the costs that he is expected to incur to implement flood-protection measures. The court dismissed Mr Lliuya’s case as no ‘linear causal chain’ could be established amid the complex components of the causal relationship between particular greenhouse gas emissions and specific climate change impacts. After his successful appeal, in 2017 the case proceeded to the evidentiary phase.

Lawyers – in particular judges – at the forefront position

As can be seen from the above cases, individuals and organisations have begun to consider courtrooms as the best place to seek much-needed answers to the global problem of climate change. Not only will states’ inability or unwillingness to combat climate change be challenged in court, but also private entities’ role in this problem will be addressed. This will place lawyers at the forefront of the fight, in particular judges, who will bear the burden of answering the question of what are states, individuals and companies actually obliged to do concerning this global issue.